Chapter OneUnearthing the Past

1970-1978

In the summer of 1970, hundreds of Japanese Americans from across the country converged at the historic Palmer House hotel in downtown Chicago. It was the biennial convention of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) , and attendees were discussing what issues the organization should tackle next.

It was here that Japanese American activists Edison Uno and Raymond Okamura introduced a bold idea: Japanese Americans should be compensated for their World War II incarceration , and the JACL should lead the effort. Beyond the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 , which was largely ineffective, it was the first public vision for reparations for the community.

The idea hit a raw nerve. Many first generation Issei and second generation Nisei didn’t talk about the wartime years because the pain, shame, and losses experienced were so profound. Some even hid the truth from their third generation Sansei kids to protect them. Why resurface traumatic memories they’d worked so hard to bury for the sake of a false hope?

Then there was the concept of reparations itself. Some community members felt it was shameful to ask for money, especially for something that happened decades ago. Others argued it was impossible to determine the value of years of lost freedom, and to give that freedom a monetary amount would cheapen its worth.

After the convention in Chicago, the debates about reparations continued into the mid-’70s. Meanwhile, the JACL undertook several campaigns related to the incarceration, including the repeal of Title II of the Internal Security Act of 1950 , the revocation of Executive Order 9066 , and President Gerald Ford's pardoning of Iva Toguri D’Aquino . These efforts laid the groundwork for relationships with congressional representatives and built momentum for a larger reparations movement.

Another factor that contributed to the growing interest in reparations was the social and political awakening of the third-generation Sansei, many of whom were learning about their family’s incarceration for the first time.

Ross Harano was one of those Sansei. He was born and raised in one of the Japanese American concentration camps before his family resettled to Chicago’s South Side after the war. It wasn’t until he attended a JACL convention in Minnesota at the age of 19 that he finally connected the dots about his unusual upbringing and his uncles’ military service in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe and the Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific.

Hear from Ross Harano

In 1973, more than a decade later, Harano traveled with a group of thirty Japanese Americans to the former site of Jerome, the camp where he was incarcerated as a toddler. It was part of the first wave of pilgrimages that served the community’s growing interest in commemorating the camp experience. Around the same time, some of the first books about the incarceration were published.

Sansei like Harano infused the movement for reparations with passion and a spirit of social protest. The Sansei generation came of age during the civil rights and antiwar movements , which shaped their understanding of race and inequality. To them, Japanese American incarceration was not just a tragedy — it was an example of racial injustice. Reparations, therefore, were part of a much larger fight for justice for all historically marginalized groups.

By the late-’70s, the idea of reparations had gained enough traction to become one of the key focuses of the JACL’s agenda. In 1977, the organization published the booklet, “A Case for Redress,” the first wide-scale effort to educate the community about its incarceration and get buy-in for reparations.

“A Case for Redress” reflected the JACL’s strategy of using the term “redress” instead of “reparations.” While monetary compensation was still at the center of the campaign, the larger goal of the redress movement was to ensure what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II would never happen again to any other group. This way, it was about more than just compensating Japanese Americans for their grievances — it was about protecting the civil liberties of all Americans.

Still, the question about money lingered. Many debated whether reparations should come in the form of individual payments or a single trust fund. One proposal called the Seattle Plan suggested a lump sum of reparations for displaced individuals plus additional reparations based on the number of days imprisoned.

In 1978, after painstaking back-and-forth, the JACL’s Redress Committee unveiled a proposal: $25,000 to every former detainee, an apology from the president, and an educational trust fund. Bill Yoshino , who served as the JACL’s Midwest Regional Director from 1978 to 2017, says the element of monetary compensation played a controversial but crucial role in the campaign.

Hear from Bill Yoshino

What were some of the factors that led the Japanese American community to consider redress and reparations for their incarceration during World War II?

Ultimately, the JACL’s national council approved the proposal calling for $25,000 in individual compensation. But this was just the first step in what would become a decade-long quest.

The road to reparations for Japanese Americans involved years of organizing and lobbying, the unearthing of traumatic memories, and heated debates over what would adequately compensate for the trauma and losses experienced.

But it also involved a much-needed reckoning with history, intergenerational collaboration, and ultimately, healing from the guilt and shame that had haunted the community for decades.

Chapter TwoThree movements form

1979-1980

In late January of 1979, the JACL tested the waters with its reparations proposal. The audience? Four powerful Japanese American members of Congress — U.S. Senators Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga from Hawaii and U.S. Representatives Robert Matsui and Norman Mineta from California.

The meeting was held in Senator Inouye’s office in the U.S. Capitol building. A group of JACL leaders presented the idea for $25,000 in individual compensation through an appropriations bill . According to John Tateishi, the National Redress Director for the JACL, Mineta and Matsunaga initially seemed receptive to the idea, but then Inouye interjected with a question.

“Have you fellows thought about a commission?”

Mineta quickly objected to the idea, but Inouye persisted. The core issue with going straight for an appropriations bill, he explained, was that Congress and the American public knew hardly anything about Japanese American incarceration. They were already facing criticism from another Japanese American senator, S.I. Hayakawa, who publicly deemed the incarceration of Japanese Americans “perfectly understandable,” although he himself never experienced incarceration. If Hayakawa and others weren’t convinced a wrong ever happened, why would they support reparations?

That’s where the commission would come in, Inouye continued. The commission would be a government-appointed group tasked with investigating the incarceration and deciding whether a legal wrong had been committed. As part of its research, the commission would hold public hearings around the country, generating publicity and furthering public education on the issue. This approach would take much longer, but it would help build the case for an eventual appropriations bill.

After the meeting at the Capitol, the JACL leaders felt conflicted. Most strongly preferred going straight for a compensation bill, but they also couldn’t ignore Senator Inouye’s warnings about the political realities in Washington. Plus, it was crucial they have the support of their Japanese American congressmen in any legislative fight.

Ultimately, the pragmatic approach won out. In March of 1979, the JACL’s National Committee of Redress voted in favor of legislation seeking the creation of a federal commission. That vote was followed by another vote including all JACL chapters nationwide, which narrowly favored the commission approach.

Almost immediately, the strategy received harsh criticism from the Japanese American community. The JACL was accused of selling out to politicians and for being cowardly and soft in its approach to reparations.

In fact, the JACL’s controversial decision to pursue a commission bill led to the rise of two other grassroots organizations, each with their own approach to redress and reparations.

Mostly based in California and New York, the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations , or NCRR, advocated for the original JACL proposal of a reparations bill. To them, monetary compensation was the most important and urgent goal of the redress movement — and they saw reparations as part of a larger movement for racial justice.

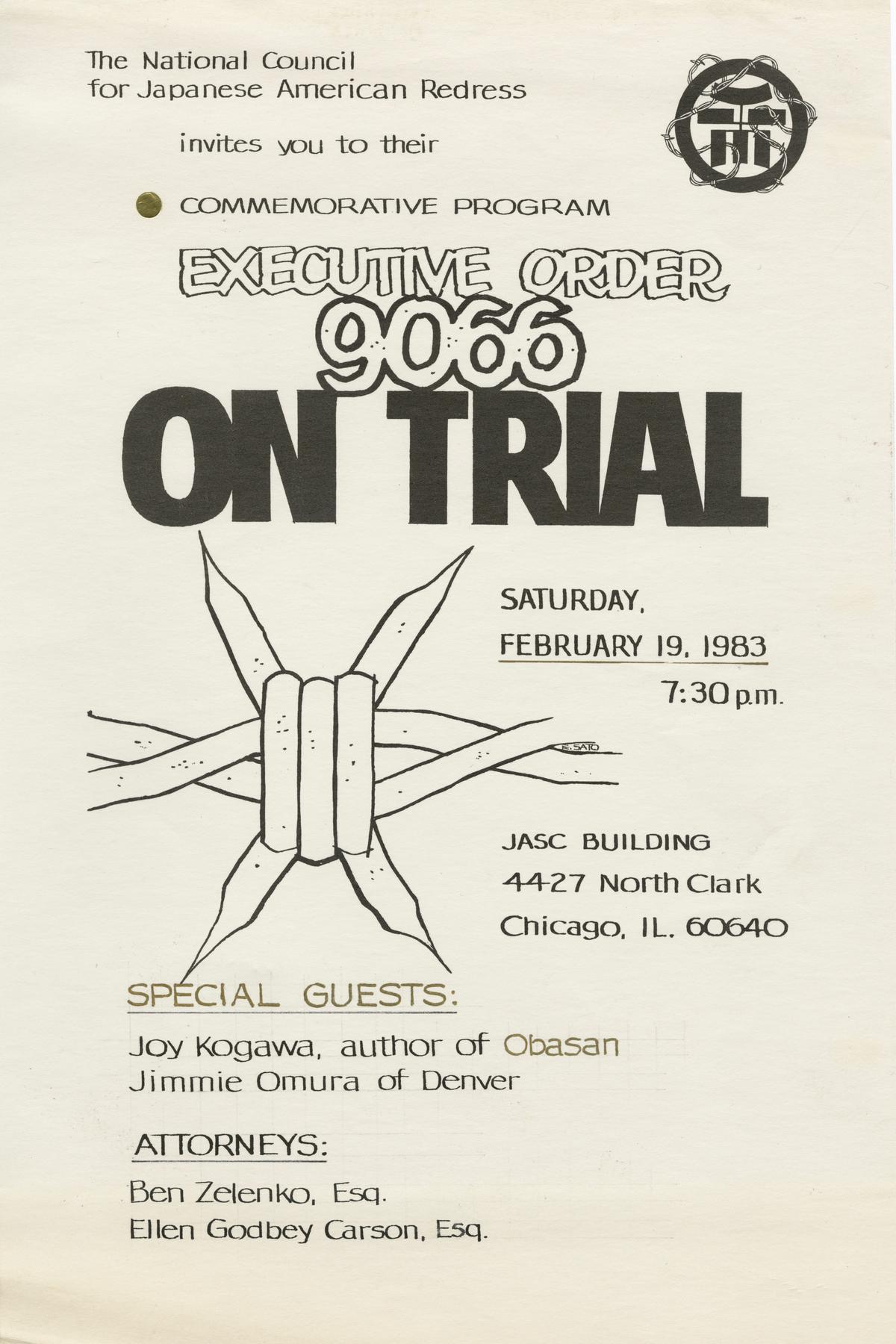

The other organization that developed around the same time was the National Council for Japanese American Redress , or NCJAR. Initially formed in Seattle, the group moved its headquarters to a Methodist church in Chicago when Chicago-based computer programmer and activist William Hohri agreed to lead the group.

NCJAR opposed the JACL’s commission bill approach and initially threw their support behind a proposed direct compensation bill that was inspired by the early Seattle Plan . After that bill died in committee, NCJAR altered its strategy of pursuing reparations through Congress. Instead, the group decided to file a class-action lawsuit to demand remedies for the government’s violation of Japanese Americans’ constitutional rights.

Former board member Mary Samson says the goal of the lawsuit was to set a legal precedent that would protect the civil liberties of other groups, and to hold the government accountable for the wrongdoings it committed.

Hear from Mary Samson

As NCJAR prepared to file its lawsuit, the Chicago chapter of the JACL was busy lobbying for a commission bill. Getting regional support for the legislation was crucial since the Midwest had far more votes in Congress than the West Coast.

Ross Harano was involved in these early lobbying efforts. He says a core challenge was convincing people that the issue was about Japanese Americans, not about Japan. It highlighted the need for education about Japanese American incarceration and the stereotype of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners .

Hear from Ross Harano

Despite these early challenges, the commission bill eventually gained enough support to pass in the House and Senate. In late July of 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed a law creating the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians , or CWRIC. The commission had two years to complete an investigation into the incarceration, a process that would involve extensive research and a series of hearings during which former detainees had the chance to testify publicly about their experiences.

With the creation of the CWRIC, Japanese Americans had overcome the first legislative hurdle. The stage was now set for them to finally share their story with the nation.

The JACL, NCRR, and NCJAR each took a different approach to redress and reparations. Which approach do you agree with most, and why?

Chapter ThreeThe power of testimony

1981-1983

For two days in September of 1981, the auditorium at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago was packed to the brim with hundreds of Japanese Americans. They’d come from all corners of the Midwest — many to share their stories, but most simply to bear witness.

Bill Yoshino could hardly believe the scene in front of him. Just a few months ago, Chicago wasn’t even included in the lineup of nationwide commission hearings. He’d fought for Chicago to be added to the schedule because he felt the Midwest community had a unique perspective to share. Tens of thousands of former detainees ended up resettling in the region.

Yoshino turned to the front of the auditorium, where the panel of nine commissioners sat at a long table. Chaired by Washington lawyer Joan Z. Bernstein , they were a distinguished group hand selected by President Carter and members of the House and Senate. Only one, Judge William Marutani, was Japanese American. The group’s composition was intentional — Senator Inouye believed that to sell Congress on redress, it was best if the commission was majority non-Japanese American.

Opposite the commissioners was a table where more than 100 witnesses would testify over the next two days. To prepare witnesses for the hearings, the JACL’s Chicago chapter hosted several workshops for people to practice delivering their testimonies in a safe space.

Chiye Tomihiro, who led witness recruitment efforts for the hearings, recalls these practice sessions were raw and emotional. Many of the witnesses were processing memories they’d suppressed for decades.

Hear from Chiye Tomihiro (Courtesy of Densho)

In the end, only a fraction of those who submitted testimonies were selected to speak at the Chicago hearings. The chosen witnesses testified about the many hardships of the incarceration experience, from the profound economic losses to the lasting psychological trauma. Veterans of the 442nd spoke about their experiences fighting on behalf of the U.S. while their families were imprisoned behind barbed wire.

The testimonies were deeply personal. Grace Watanabe Kimura recounted the heart-wrenching experience of leaving her dying father behind when she and her siblings were forcibly sent to the desert. Shiro Shiraga talked about how he gave an impassioned speech about patriotism and the Constitution for his high school commencement address, only to find himself incarcerated in a horse stable a couple of months later. Shizu Sue Lofton described how hard she tried to make the long journey to Manzanar an adventure for her 2-year-old. After stepping into the family’s designated barrack, her daughter announced, “Let’s go home now, Mommy.”

Bill Yoshino says the hearings became a form of collective catharsis for the community.

Hear from Bill Yoshino

The hearings also included elements of resistance. Reverend Jitsuo Morikawa used his testimony to denounce the hearing process, arguing that capping witness statements to 5 minutes was just another form of injustice towards Japanese Americans. NCJAR board member Merry Fujihara Omori walked out of the auditorium after she was cut off before finishing her testimony.

Some NCJAR members stood at the beginning of each testimony as a form of protest, and urged others to do so too — they believed there was sufficient evidence of an injustice and found it unnecessary to ask victims to relive their trauma. After the hearings, though, Hohri wrote that he couldn’t deny the role they played in the community’s healing process.

View videos and read written transcripts of the Chicago testimonies.

Including Chicago, the commission held 20 days of hearings in ten cities across the country. More than 750 witnesses testified, a group that included former detainees, constitutional scholars, and the government officials responsible for the incarceration. To supplement the testimonies, lead commission researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and her husband Jack Herzig found and organized primary government documents that formed the core of the commission’s findings.

In February of 1983, the CWRIC published its findings in a damning report titled “Personal Justice Denied .” It called the incarceration a “grave injustice” not determined by military necessity but rather the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

Due to time limits, only a fraction of the people who submitted testimonies were invited to testify, and only for 5 minutes each. How would you have structured the 2-day hearings?

Four months later, the commission issued its recommendations for redress. The proposal included a formal apology, an educational trust fund, and $20,000 for each living survivor of the camps. It wasn’t the $25,000 that the JACL initially proposed, but it was a call for monetary compensation nonetheless. The total costs of implementing the recommendations were estimated to be around $1.5 billion.

Ross Harano says the strength of the commission was that the official proposal for reparations didn’t come from Japanese Americans — it came from the U.S. government itself.

Hear from Ross Harano

Because of the commission, the decades-long silence around the incarceration was broken and the evidence of an injustice was incontrovertible. The next step was to push for a reparations bill.

Chapter FourLegal and legislative battles

1983-1990

Thirteen years after Edison Uno and Raymond Okamura gave their speech at the Palmer House Hotel in Chicago, the idea for Japanese American reparations had grown from a distant hope into a true possibility. With the commission’s work complete, the battle was now about pushing Congress to pass redress legislation. The bill would require a majority in both the House and Senate.

The political climate of the early 1980s, however, presented unexpected challenges. The country was in the midst of a deep recession, and the 1980 election of President Ronald Reagan ushered in an era of tax cuts and reduced government spending. Republicans had also gained control of the Senate for the first time since 1954. For Congress, the idea of spending $1.5 billion of taxpayer money on a redress bill was not so appealing.

At the same time, Japan was experiencing explosive growth in its manufacturing and technology sectors, threatening U.S. economic domination. Many blamed the decline of the U.S. auto manufacturing industry on the rise of Japanese car manufacturers. Consequently, Asian Americans became scapegoats for the country’s economic hardship.

During this time, the Midwest became a flash point for anti-Asian sentiment and violence since the region’s economy depended heavily on manufacturing giants like Chrysler and GM. In some cities, people smashed Japanese cars with baseball bats to express their anger. Then, in the summer of 1982 in Detroit, a Chinese American man named Vincent Chin was beaten to death with a baseball bat. His killers were two white auto workers who mistook him for being Japanese.

It was within this environment that the JACL had to convince members of Congress to support a redress bill. In the Midwest, Bill Yoshino and Ross Harano urged city and state representatives to pass local resolutions in support of a redress bill.

What challenges did the Midwest Japanese American community face in getting widespread support for a redress bill?

Harano said his history of interracial activism helped him build a broad coalition of support for redress in the Midwest.

Hear from Ross Harano

While the JACL was busy lobbying for a redress bill, new legal developments furthered support for the redress movement. Between 1983 and 1987, Fred T. Korematsu , Gordon K. Hirabayashi , and Minoru Yasui petitioned to have their historic Supreme Court cases reopened. The process they used was a writ of error coram nobis , a legal order allowing a court to correct its original judgement.

The impetus for the petitions was groundbreaking research by legal scholar Peter Irons and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga , the lead commission researcher who was also a supporter of NCJAR. The two discovered documents proving the U.S. army had seen no “military necessity” to incarcerate Japanese Americans. Their research also revealed the Department of Justice deliberately suppressed evidence to mislead the Supreme Court. The coram nobis cases put Irons’ and Herzig-Yoshinaga’s findings into the public spotlight and helped discredit arguments that the incarceration was justified.

The same research that fueled the coram nobis cases also formed the backbone of NCJAR’s class action lawsuit. Filed in the spring of 1983 with William Hohri as the lead plaintiff, the lawsuit sought $27 billion in damages from the incarceration, a figure that reflected both the value of property losses and the value of constitutional and civil rights violations.

In 1987, the case went before the Supreme Court but was eventually dismissed on a technicality. Nevertheless, NCJAR supporters later felt the lawsuit had been worth pursuing because it was important to hold the government accountable and because it fueled important research about the incarceration. Additionally, some congresspeople admitted that the pending $27 billion lawsuit compelled them to support the redress bill, which had a much more moderate $1.5 billion price tag.

As NCJAR’s lawsuit was making its way through the judicial system, the redress bill was gaining an increasing number of cosponsors in both the House and Senate — but still not enough support to make it out of the respective subcommittees. In 1985, the bill was reintroduced by Democratic House majority leader Jim Wright as “H.R. 442 ,” a reference to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most decorated U.S. military unit for its size and length of service. The following year, Democrats regained control of the House and Senate and appointed new subcommittee chairs who were sympathetic to the cause of redress. It was the perfect window of opportunity.

How did the coram nobis cases and NCJAR lawsuit contribute to the overall redress movement?

The groups that had sometimes been at odds were united during the leadup to the votes in Congress. The Japanese American members of Congress spoke one-on-one with their colleagues about what the bill meant to them personally. The JACL used its Washington connections to build more legislative support for redress. During the summer of 1987, NCRR arranged for 120 Japanese Americans of all ages and backgrounds to visit members of Congress. At the time, it was the largest Asian American lobbying campaign to converge in D.C. in a concentrated period of time.

In September of 1987, on the 200th anniversary of the signing of the U.S. Constitution, the House passed H.R. 442 with a majority vote. The following April, the Senate passed a similar bill by a two-thirds margin. Finally, on August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed H.R. 442, also known as the Civil Liberties Act , into law.

In 1990, almost half a century after their imprisonment during World War II, the first group of elderly Japanese Americans received their apology letters and $20,000 checks. The long journey towards reparations was finally over.

Chapter FiveReckoning with racial injustice today

1990-today

The movement for redress and reparations had a profound effect on the Japanese American psyche. In the years after the passage of the Civil Liberties Act, many Nisei started talking openly with friends and family about the war years for the first time. In Chicago, there was a surge of interest in documenting and sharing the community’s history. In the early 1990s, local leaders founded the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society, which led the Chicago portion of “REgenerations,” an oral history project of the Japanese American National Museum supported by the redress educational trust fund. The Chicago JACL chapter also recruited Nisei to speak to school classes about the incarceration.

Former JACL Chicago president Jane Kaihatsu, who helped with redress efforts, says the movement had an invaluable effect on the community’s ability to tell its story with the larger public. Without it, Japanese American incarceration would have been a missing chapter of American history.

Hear from Jane Kaihatsu

In the early 2000s, the Japanese American story gained new relevance. On September 11, 2001 — sixty years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor — militants associated with the Islamic extremist group Al-Qaeda flew planes into the Twin Towers in New York and the Pentagon building in Arlington, Virginia. Also known as 9/11 , the attacks killed nearly 3,000 people and injured thousands more.

As the terrorists were identified, Bill Yoshino felt an eerie sense of déjà vu as Arab and Muslim communities in the U.S. quickly became targets of suspicion and hate. Just like Japanese Americans, they were visible scapegoats for an attack by a foreign enemy.

At the time, Yoshino was leading the JACL’s anti-hate crime initiative. He says the September 11 attacks compelled many older Japanese Americans to publicly share their stories. Yoshino credits the redress movement for emboldening Japanese Americans to speak up on behalf of other communities.

Hear from Bill Yoshino

In recent years, the organizing and activism work within the Chicago Japanese American community has expanded beyond supporting Arab and Muslim communities. In 2019, several Japanese American organizations led an Asian American coalition protesting the family separation and indefinite detention of migrants from Central America seeking asylum in the U.S. In 2020, as part of a larger national social justice movement called Tsuru for Solidarity , several dozen Chicago Japanese Americans hung paper cranes at the Cook County Jail to protest mass incarceration and police brutality toward Black and brown people. Since then, members of the local organization Nikkei Uprising have committed to prison and police abolition causes in Chicago, including regular demonstrations at the jail.

Chicago JACL chapter president Lisa Doi says she and other community members continue to make connections between Japanese American incarceration and a broader pattern of racial injustice in the United States.

Hear from Lisa Doi

In 2020, the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery sparked conversations around racial justice and the need to reckon with the country’s legacy of slavery and discrimination.

In particular, there was renewed interest in H.R. 40 , the first legislative proposal for reparations for the African American community. The bill was first introduced in Congress in 1989 — less than a year after the signing of the Civil Liberties Act — by the late Representative John Conyers, the longest serving African American member of Congress. Conyers modeled the bill after the Japanese American reparations strategy. If passed, it would establish a commission to study the history of slavery and discrimination in the U.S. That commission would also develop proposals for reparations for African Americans.

The bill has been introduced every year since 1989, but it wasn’t until early 2021 that it gained enough traction to receive a proper congressional hearing. In anticipation of that hearing, members of Congress and supporting organizations asked Japanese Americans to write testimonies in support of the bill.

In April of 2021, the bill cleared the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary and is heading to the floor of the House of Representatives for a full vote.

Doi says the act of writing testimonies — this time in support of reparations for a different community — was a powerful exercise for Japanese Americans.

Hear from Lisa Doi

In addition to pushes for federal legislation, there have been other local reparations efforts in the Chicago area. In March of 2021, the city of Evanston, Illinois approved a reparations program that grants $25,000 in housing assistance to certain African American residents or their descendants harmed by past discriminatory housing policies. The program makes Evanston the first city in the U.S. to pay reparations to African American citizens.

While Doi acknowledges the significance of legislation like the Civil Liberties Act and local reparations efforts like the one in Evanston, she believes they still fall short of true repair. As the Japanese American community has learned by experience, this process also involves community dialogue, education, and storytelling.

When it comes to reckoning with an injustice as great as slavery, Doi says she’s hopeful that all Americans — especially Japanese Americans — will play an active role in that process.